Anguish: BBC Correspondent Malcolm Brabant with his wife Trine and their son Lukas outside their new home in Copenhagen

Before wielding the syringe, the middle-aged nurse in the scruffy Greek prefectural office warned me to expect symptoms similar to mild influenza.

But nothing could have prepared me for the catastrophic adverse reaction that I endured and which has left me a ruined, broken man.

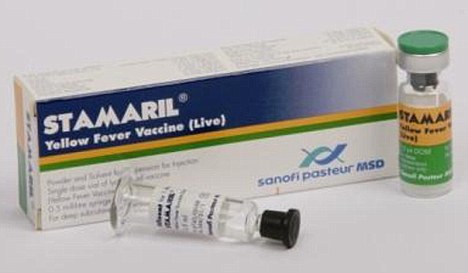

Stamaril, the yellow fever vaccine made by Sanofi Pasteur, one of the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies, is credited with saving hundreds of thousands of lives. But the jab fried my brain and transported me to within a whisper of death and paralysis.

Anguish: BBC Correspondent Malcolm Brabant with his wife Trine and their son Lukas outside their new home in Copenhagen

It has taken my little family and me to the gates of hell. Since April, I have spent more than three months in the intensive care units of psychiatric hospitals in three countries, and there is a possibility that I will never fully recover.

(Malcolm has had three psychotic episodes. In between, he is lucid, aware that he has endured a period of serious mental illness. He can remember most of what has happened to him during the psychotic episodes. He also keeps a diary and has been filmed frequently. This account was written last week, during a lucid period.)

I needed the inoculation as protection against mosquitoes that carry the yellow fever virus and kill an estimated 200,000 people each year in sub-Saharan Africa and South America. I was due to fly to Ivory Coast to shoot a series of films about victims of the country’s civil conflict for Unicef, the United Nations children’s fund. It was supposed to be my second assignment for Unicef TV, an organisation that requires sensitive videography and story-telling.

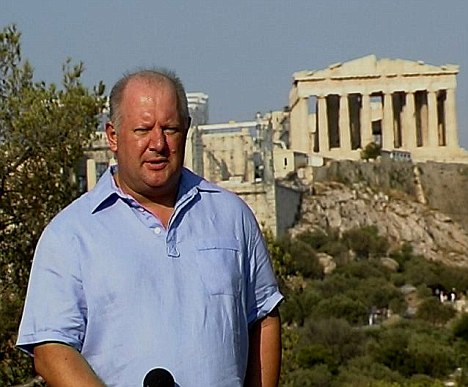

I have been a freelance BBC foreign correspondent for 22 years and had been in Athens for the previous eight years, with none of the benefits enjoyed by journalists on the staff.

Well respected: Malcolm Brabant was the BBC's Athens correspondent - but was unable to report on rioting in the Greek capital due to his illness

Work and money was scarce at the start of the year because of the BBC’s focus on the Arab uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa. Interest in the Greek financial crisis had waned. So I leapt at Unicef’s offer to fly to West Africa.

But the immunisation made me too sick to travel. Within 24 hours of the jab, I was confined to bed with a temperature of 103.6F (39.8C). We knew instantly this was a reaction to the inoculation, since no one else was sick and nothing had happened to me apart from the vaccination. I was shivering and rocking the bed so violently that it slammed against the bedside table.

My wife, the Danish author Trine Villemann, couldn’t believe the severity of the fever and changed thermometers. The second thermometer confirmed the first reading. I was gripping on to the duvet for dear life because I was simultaneously freezing and drenched in a cold sweat.

Trine applied over-the-counter medicines such as Ibuprofen to try to suppress the fever but my temperature hovered resolutely at 104F (40C) and on occasions spiked as high as 104.5F (40.3C).

The body’s normal temperature is 98.6F (37C).

Petition: Mr Brabant's wife, Trine Villemann is now trying to obtain the findings of an investigation

I had a battery of examinations in hospital and was admitted when my liver test produced an abnormal result.

The fever was depriving me of sleep and the insomnia left me emotionally exhausted.

I suffered my first hallucination 11 days into what was now a severe illness that was baffling Greece’s top infectious diseases experts. I was convinced my Kindle e-book reader flew across the hospital room from the bed to a chair.

Despite being a veteran, cynical journalist, I started to believe that I had supernatural powers.

Thirteen days after the shot, doctors began giving me steroids to try to dampen the fever. At long last, they succeeded. But my mental downward spiral steepened the next day, Friday, April 29, the day Prince William married Kate Middleton.

I was watching the ceremony on television with Trine, who has written two books about the Danish royal family. This was supposed to be a treat for her because of her professional interest.

But I spoiled the occasion. Every time I saw someone in uniform, I jumped up and saluted. I was in floods of tears and in hyper-patriotic mood at witnessing a British ceremony at its finest, weeping over the flowers and the music.

Trine never got to see the Royal couple say ‘I will’. She switched off the television because she thought I was too distressed.

She ordered me to have a rest and left my room. When she returned an hour later, I was still sobbing.

Later that day, I became convinced that I was the Messiah. The trigger was a midnight email from Bob Traa, the head of the International Monetary Fund team in Athens, who was agreeing to a highly prized off-the-record meeting about the Greek economic crisis. I was delirious. I never thought he’d see me.

I sent back a crazed reply saying: ‘I’m getting very tired now. I need to sleep because we have a lot of work to do. One thing I will say is that Greece has really been kind to me and it has cured my son.

‘It is God’s country. Its people are fantastic. Sorry, the bed is shaking.God bless. Malcolm.’

Indeed, the bed was pitching so violently, I thought it was a sign from Heaven that the second coming had begun. A few days later, Trine transferred me to the Sinouri Clinic, a poor Athenian imitation of Britain’s Priory. ‘You had called me and told me you were Jesus,’ she says.

I was sitting on the windowsill of my room on the 15th floor of the hospital, looking towards the dome of an Orthodox church. ‘I am going to fly with the angels,’ I said.

Apparently, it is quite common for the insane to be convinced that they are Jesus Christ. My experience in Athens in April and May was similar to that of Jim Carrey when he played an ordinary American who suddenly developed divine powers and became Bruce Almighty in the movie of the same name.

There were times when I was confused about whether I was Christianity’s Joseph figure or the Messiah himself. It was excruciating trying to persuade Trine that our son Lukas was in line to save the world like me.

‘Do you know who I am?’ I used to beg.

‘Yes, I know who you are,’ she would reply. But her eyes told me she didn’t believe me.

I thought I had been chosen because of my understanding of the media and new technology. I decided to test my powers and flushed my Kindle in the lavatory, then picked it up and turned it on. The display flickered briefly and then it expired permanently. I thought perhaps this was just teething trouble and was certain that other miracles would ensue.

For a week, I disappeared into a mental black hole and had no inkling of just how mad I had become. Then, gradually, I returned to consciousness and became self-aware.

Bad reaction: The Stamaril vaccine that Malcolm took

But during the psychotic episode, I became convinced that the British Government knew that I was the Messiah and had put cameras in the bathroom of my room in the psychiatric ward. I spent hours in the bathroom denouncing various Greek politicians for being corrupt.

I was sure that a video-feed from the bathroom was being played to 10 Downing Street, Buckingham Palace and the White House. During one session, I was certain that the Queen Mother had returned from the dead and was roaring with laughter at my antics.

I interpreted ‘messages’ that meant the British Royal Family was going to step aside so that Lukas could become King and could have the protection the next Messiah would require.

I was getting messages from the dead people that, during the sane period of my life, I have always regarded as my guardian angels. They included my son James, who would have been 33 years old this year and who died in his pram of cot death when he was just four months old.

I would get an electronic buzz when the guardian angels wished to speak. The spirits ‘on the other side’ included Danny McGrory, one of my best friends in journalism, who died of a sudden stroke; Kurt Schork, a Reuters correspondent who was killed in Sierra Leone during the civil war; Terry Lloyd, the ITN reporter killed in Iraq, who had given me my first job in journalism; and Bill Frost, a brilliant Radio 4 correspondent who died prematurely young.

They set me a series of tests, and were cackling with laughter as they

commanded me to drink my own urine from the porcelain bowl and to clean my teeth

with a toilet brush. I complied with their demands. Urine doesn’t taste as bad

as you might think, but I refused to go along with my guardian angels’ most

outrageous demand – to eat my own excrement. ‘There are limits, chaps,’ I said.

Emotional moment: The Royal wedding in April put Malcolm in a 'hyper-patriotic mood'

It was excruciatingly frustrating trying and failing to convince anyone that I was the next Messiah. I tried to recreate the stigmata by squashing fresh strawberries, brought to me by my wife, and painting ‘blood marks’ on the wall of the bathroom. I commanded her to dress me up in a nappy made from a sheet so I could lie in bed like a divine infant. I also insisted she polish my halo.

The owner of the Sinouri Clinic, a psychiatrist called Pantelis Lazaridis, declared that I had suffered what he called ‘an acute organic psychotic event’.

Throughout my illness, Trine was conducting an investigation into the cause. We both knew the trigger was the yellow fever inoculation. A specialist at the London Hospital for Tropical Diseases said he suspected the jab was contaminated. Professor Eleni Giamarellou, Greece’s leading specialist in infectious diseases who treated me at Athens’ Ygeia hospital, believes I was hypersensitive to the drug and suffered an allergic reaction to it.

Despite the devastating impact on me, the Greek health authorities have displayed no interest in investigating whether other syringes were contaminated. Sanofi Pasteur denies there is any link between my illness and its vaccine.

The company is also asking for more data and claims we have prevented its investigators from having access to my medical records. That is simply not true. My wife sent the company an email giving them permission to talk to Professor Giamarellou and Dr Laziridis.

With the help of anti-psychotic drugs, prescribed by Dr Laziridis, I returned to sanity in time to be able to vigorously cover the Greek economic crisis for the BBC in June.

But there was no escape from the devastating impact of Sanofi Pasteur’s vaccine.

In July, I found myself sectioned in a secure psychiatric ward in Ipswich, the town where I grew up.

I had returned to Britain because I lost faith in the efficacy of Greek psychiatric care. The specialists in Ipswich decided I needed to be protected from myself after I suffered a major relapse and displayed more bizarre behaviour.

I escaped from a psychiatric crisis team. Wearing excessively tight Lycra shorts and jacket, I took my bike on the train to London, with the aim of acting as a peacemaker in the BBC journalists’ strike. I demanded to see the director-general and the strike leader.

As I was being gently shepherded out of Television Centre to a BBC car to take me back to Ipswich, I spotted Frank Gardner, the BBC’s security correspondent, who is partially paralysed after being shot in Saudi Arabia in 2004. I told him about my Messianic convictions and rubbed his back in the hope of accomplishing a miracle cure.

Frank was really graciously indulgent and said: ‘I’ll take whatever I can get.’

My performance in front of senior BBC managers and other colleagues demonstrated that I was certifiable and reinforced the stigma attached to mental illness.

But it isn’t just me who has suffered. Trine and son Lukas have also been tormented by my psychotic episodes.

Lukas has witnessed things no 12-year-old should see, such as my episode in July when I thought I was being targeted by the Greek government. Trine had to quickly get him out of our house in Athens as I ranted and raved, wearing a helmet and a bulletproof jacket over the top of a stab vest.

‘How are we going to survive if Dad dies?’ he has asked his mother on more than one occasion.

We have been forced to move from Greece to Denmark because of my illness. The health care here is free. We have also come here in the hope that Trine can find a job to support us. So far, she has been unsuccessful because she has spent all her time caring for my needs.

Lukas has been wrenched from a happy international school in Athens and forced to abandon his pack of lifelong friends. He has been separated from his beloved labrador Dash, as dogs aren’t allowed in the block where we rent a small, shabby apartment. Dash has been farmed out to Lukas’s wonderful grandmother, who lives 20 miles outside Copenhagen, and our son is lucky if he is able to see his pet once a week.

‘I hate Denmark,’ is Lukas’s occasional refrain. ‘I want to go back to Greece.’

Such an option is not possible.

It breaks my heart to see my charming, upbeat son looking pale, with rings around his eyes. He’s become withdrawn and defiant. I just hope that he is not permanently damaged. Yet, despite being forced to give up so much, he doesn’t blame me for what has happened.

His first question to his mother as soon as he sees her is always: ‘Is Dad OK?’

My beautiful wife Trine, the love of my life, whom I met in Sarajevo 16 years ago, is ageing before my very eyes as she acts as the glue binding our family together – trying to present a facade of normality for Lukas while being my nursemaid.

‘I want my life back,’ she wept the other day as she once again drove me to the psychiatric facility in Copenhagen that has been treating me since the beginning of November when I suffered my third psychotic episode after having Sanofi Pasteur’s vaccine.

This time, I became obsessed that I was the Devil. Again I vanished into a black hole where I lost all conscious thought. It lasted a week or so and poor Lukas witnessed that horrific slippage.

‘I want my partner back, I want my best friend back,’ my wife cried.

I was discharged from the Copenhagen psychiatric facility in the week before Christmas because my supervising doctor thought I was the sanest person on the ward. Trine struggled to contain her anger as she unsuccessfully argued that my release was premature.

Three days later, I was readmitted so the doctors could adjust my medication. I wrote this article while I was at home and in the real world.

So I am once again trying to take baby steps back towards normality and hoping I can cope.

I am also fighting pulmonary embolisms and deep-vein thrombosis, which have suddenly appeared in the atrophying hospital conditions. The first psychotic episode in Athens almost killed me and now lethal physical reinforcements have surfaced.

Death, my death, has become a subject we feel we no longer have the luxury of ignoring. The other day, Trine and I took a walk in a park next to our new Copenhagen home, which turned out to be a cemetery.

‘If I die,’ I said, ‘I’d like to be cremated.’ She interrupted me.

‘I have been forced to think about this,’ she said, ‘and I will demand a post-mortem to try to find out what happened to you because we are not getting answers from Sanofi Pasteur.’

‘Then you can burn me,’ I said. ‘And scatter my ashes in Sarajevo or Santorini [the exquisite Greek island where Trine and I married for better or worse].

‘Your choice,’ I added.

But I have so much to live for. Anyone who knows me will testify that I am a fighter with a naturally cheerful, optimistic, stubborn disposition. I will do my damnedest to return from the gates of Hades and escape this Kafkaesque existence brought on by one little prick with a syringe containing Sanofi Pasteur’s yellow fever vaccine.

If you think that sounds like the ramblings of a madman, you are officially wrong.

‘What has happened to you is a terrible tragedy,’ said my supervising Danish doctor.

‘But you have a good chance of a full recovery because of the strength of your character.’