By Jo Waters

|

Jean Smith felt as if a thick fog had descended on her brain as once again she found herself having to re-read sentences three times so she understood what they meant.

‘Even when I talked I struggled to find the right words,’ recalls Jean, a 63-year-old former civil servant, who lives in Liverpool with her husband, Kenneth, 58, a factory supervisor.

‘I told Kenneth the same things over and I never knew what the day was.

'I just couldn’t think clearly and was worried I was beginning to lose it.’

She was also sleeping more than usual.

In fact, Jean’s brain was absolutely fine — the real problem was the dozens of medications she’d been prescribed by her GP.

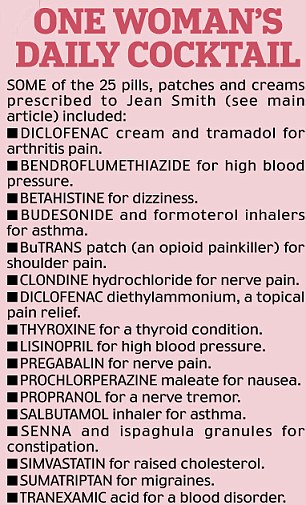

Jean was on a cocktail of more than 25 pills, patches and creams a day, from an anti- hypertensive drug for high blood pressure to painkillers for arthritis.

The prescriptions had increased during a 15-year period.

‘The effects built up gradually as my prescriptions escalated. I felt I was under a chemical cosh,’ recalls Jean.

‘To be fair, my GP is pretty good at checking up on how I get on with new drugs — the problem is like most people I just wasn’t aware that some of the symptoms I had were actually side-effects of drugs.’

But last November, after Jean experienced dizzy spells and sudden low blood pressure, her doctors and GP decided to reduce her drugs down to just nine.

‘They were unsure whether my symptoms were linked to a new medical condition or were a symptom of drug interactions. It actually turned out to be a combination of both.’

For although the bad news was that Jean had another problem — an autoimmune condition affecting her adrenal glands — coming off some of her drugs actually cured her memory problems.

‘I can think clearly again and I’m not forgetting things,’ she says happily. ‘I don’t feel like I’m drugged up to the eyeballs any more.’

Jean is one of a growing number of patients in the UK on a daily cocktail of drugs to treat medical conditions, prevent others and increasingly, to deal with the side-effects of prescribed medication (in other words, the drugs they are given for their genuine ailments in turn create symptoms).

The annual number of prescriptions per head of population has increased from 11.9 in 2001 to 18.3 per person in 2011.

Most of this increase has been in prescribing for the elderly. Almost half the over-65s have three chronic health problems, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and arthritis. It’s quite common for this age group to be taking eight to 12 different types of medication daily.

Taking lots of different prescription pills and medicines — known as polypharmacy — is a major issue for this age group, says Dr Chris Fox, consultant old age psychiatrist at the Norfolk and Suffolk Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust and a senior lecturer at the University of East Anglia.

Experts warn the problem is partly due to prescribers being too quick to medicate — without always checking what other medication the patient is already on. As we shall see, GPs are also effectively incentivised to put patients on pills.

Elderly patients often don’t know why they are on so many drugs, says Dr Trisha McNair, specialist in medicine for the elderly at Milford Hospital, Surrey: ‘One GP friend of mine says she had a patient who kept all her pills on a huge glass bowl on the kitchen table and just took a random handful when she was passing.’

Dr McNair says she often sees patients who are on between 12 and 20 different types of medication, including pills, sprays and creams.

THE DANGER OF SIDE-EFFECTS

The problem with polypharmacy is that the more drugs you take, the more likely you are to experience side-effects that are then misinterpreted by the healthcare practitioner as a symptom of disease that needs treating with additional medicine, explains Dr Fox.

‘Many older people on beta-blockers for blood pressure, for example, will report depression.’

This could be because depression is a known side-effect of beta-blockers.

But some patients may not need the beta-blockers at all — the problem is the drug then slows down their heart too much and it is this that makes them tired and depressed.

‘This may lead to them being prescribed anti-depressants they don’t need.

'Others who are on statins might suffer from muscle pain and this may mean they need painkillers, which may then have more side-effects, including gastric problems, which then necessitate more drugs.

‘A lot of these drugs do prevent illness, it’s true, but there is often a price to pay in terms of side-effects.’

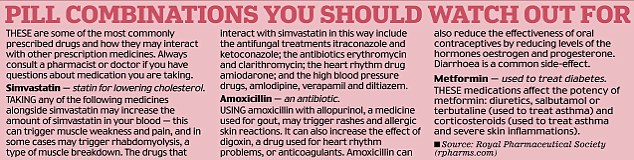

It’s not just that the drugs can cause side-effects — there’s also the problem of them interacting with each other.

‘A big part of our workload is sorting out whether these patients’ symptoms are an illness or a result of drug interactions,’ says Dr McNair.

This task is not helped by the fact that drugs are not tested on patients who are on multiple pills for different conditions, adds Dr Fox.

‘I was always taught that if you take more than three drugs at a time you can expect interactions — but these days it’s not unusual for the over-65s to be on five or more different drugs for three or more chronic health conditions. No one really knows what the cumulative effects of this are yet.

‘Although GPs use computerised prescribing systems that should flag up drug interactions, they may also write paper prescriptions on home visits and not have access to this, so the system is not infallible,’ says Dr Fox.

The elderly are more at risk of drug side-effects because their metabolism is slower, meaning drugs build up in their systems, he adds.

Dr Fox recently published research that suggested commonly prescribed anticholinergic drugs — used for treating movement disorders, incontinence and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — are associated with cognitive decline in the elderly and an increased risk of death.

An estimated 20 to 50 per cent of all over-65s are being prescribed at least one anti-cholinergic drug, and while the effects of some are small, their cumulative effects may cause significant mental deterioration in older people who already have some cognitive problems, warns Ian Maidment, a senior lecturer at Aston University’s School of Pharmacy and joint author of the study.

‘Doctors can definitely do more harm than good by prescribing too many drugs

— GPs are ideally placed to take a holistic view of the patient’s overall

health, but they are hard-pressed.

‘And sometimes the patient is under four or five different specialists and it

can be hard for GPs to find out why a patient has been prescribed a particular

drug, so they tend to leave them on it.’

‘We need more research into poly-pharmacy to see what the effects are. It requires a co-ordinated response from community pharmacists, patients and their carers too.’

There is an added problem with patients self-medicating with over-the-counter drugs and herbal remedies, says Dr Fox.

Tackling polypharmacy can make a significant difference, as Jean Smith discovered.

Her experience is borne out by an Israeli study in 2010 that found that when the elderly patients in a nursing home were taken off some of their medication (under supervision), 88 per cent reported improvements in their overall health.

Fifty-six of the 70 participants reported improvements in their cognitive health.

PRESSURE TO PRESCRIBE

A major impediment to reducing polypharmacy is that the payment system for GPs effectively rewards it, says Dr Margaret McCartney, a GP from Glasgow and author of The Patient Paradox: Why Sexed-Up Medicine Is Bad For Your Health.

Under changes introduced by the Department of Health in 2004, GPs’ pay is linked to managing specified medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma, obesity and smoking.

‘The problem is GPs are judged according to the number of patients they put

on tablets,’ argues Dr McCartney.

‘A lot of elderly people feel pressured into going on to tablets, and when

you talk to GPs they, too, are fed up with the system and would embrace the

chance to practise more holistic medicine where they can use their professional

skills more.’

Tellingly, a review conducted by the University of Sydney which looked at

nine studies where elderly people had been taken off medication, concluded that

between 20 per cent and 85 per cent of patients taken off blood pressure pills

had normal blood pressure and did not need to go back on the pills, and there

was no increase in deaths as a result.

Jean Smith is grateful her doctors reviewed her medication, after seeing the

effect polypharmacy had on her father, Robert, who died last year at the age of

87.

He was on 12 different drugs, including statins, blood pressure tablets,

omeprazole for stomach acid and gabapentin for nerve pain.

‘My father was as sharp as a needle and worked as a code-breaker at Bletchley

Park during World War II,’ says Jean.

‘But in the last years of his life he began suffering greatly from the

side-effects of blood pressure pills and statins — he complained of fatigue and

kept forgetting things. His hospital specialist just told him he was old and

suggested he was depressed.’

But when Jean persuaded her father’s specialist to reduce his blood pressure

pill dose and take him off the statins, Robert felt normal again.

‘It was only after he was admitted to hospital as an emergency for a fall

that he was put back on the pills.

'He died two months later of heart failure and his geriatrician told me

quite simply that the doctors had treated him with the best of intentions but

had “overmedicated him”.

‘I think Dad had a few years left in him. I find it heartbreaking that he

died because of this obsession with putting everybody on pills. I don’t want

that to happen to me.’

Dr Fox says that, to avoid this, he thinks patients on more than five

medicines should have them reviewed ‘at least annually’.

‘The days of leaving patients on long-term medication without review should

not happen any more.’

For patients or relatives of patients taking lots of prescriptions, he

suggests asking their GP or community pharmacists for a prescription review and

discuss any drug side-effects with them — however, patients should not stop

their medication suddenly without medical advice.

For advice and information on living with a long-term condition, go to expertpatients.co.uk