YOUR stories of forced adoption: When we revealed the agony of mothers made to give up their babies, the response from readers was huge - and heartbreaking

17 April 2015

Last month, the Mail published a series of powerful articles describing the trauma and torment suffered by unmarried women forced to give up their babies for adoption from the Fifties to the Seventies.

The pieces provoked an outpouring of emotion by readers — from mothers whose babies were torn from their arms to grown-up children desperate to find the women who had been forced to give them up. Here are just some of their heartbreaking stories . . .

Readers have sent in dozens of heartbreaking stories, including mothers whose babies were torn from their arms to grown-up children desperate to find the women who had been forced to give them up

CRUELTY THAT LEFT ME WITH A LIFETIME'S GUILT

Susan Smith, 61, Lancaster

The stigma and devastation still haunts me, at the age of 61.

I was 13 when I got pregnant in 1967, and my boyfriend was 14. Neither of us had any idea what we’d done, and it was the headmistress at my school who first worked it out. By then I was nearly seven months gone and holding my school skirt in place with a nappy pin.

I found myself in a courtroom almost immediately, still in my school uniform. I was sentenced to two years’ ‘supervision’ and my boyfriend to six months in borstal. Pausing only to put on a bell tent dress, I was taken, alone, to St Monica’s Mother and Baby Home in Kendal, Cumbria, which was run very strictly by nuns.

It was a workhouse, really. The dormitories were barren — no curtains or lockers or comforts of any kind. On Thursday night we had to attend a religious service as a kind of penance. We did hard housework all day, no matter how pregnant we were.

The worst of the chores was nappy sluicing; you were dragged out of your bed at 5am and sent down to the basement where you stood at big stone sinks — I had to stand on a step to reach them — and scrubbed all the soiled nappies. There was no heating down there and you weren’t given breakfast before you did it.

The birthing room was upstairs and it sounded like a torture chamber. None of us were told what to expect, or given any medical information, which seems totally barbaric now. You’d hear other girls screaming, and just plug your ears. The fear was immeasurable.

The way I understood it, the adoption of my son was part of my ‘sentence’. I certainly don’t remember signing any papers giving permission for him to be taken. On the birth certificate, I was described as a ‘schoolgirl’ and the father’s identity was left blank.

At six weeks, he was gone. One day a car came and I was told to put him in a dress for his new parents.

The extraordinary cruelty of it still shocks me. It shaped my life. I’ve never met my son, but not a day goes by when I don’t think of him. I didn’t have another child, and I’ve never been free of the guilt.

WHEN THEY TOOK MY GIRL I FROZE

Jennifer Evans, 69, North London

I fell so deeply in love with my baby when she was born that I resisted with all my strength the pressure to give her up. But my story does not have a happy ending.

It was 1968; I was 23 and unmarried. Once I became pregnant, my boyfriend of two years simply disappeared and my family, who were wealthy and could have helped me live an independent life with my daughter, pushed me to give her away.

When I was seven months pregnant I moved into a home for unmarried mothers and babies in Wimbledon, run by the Church of England.

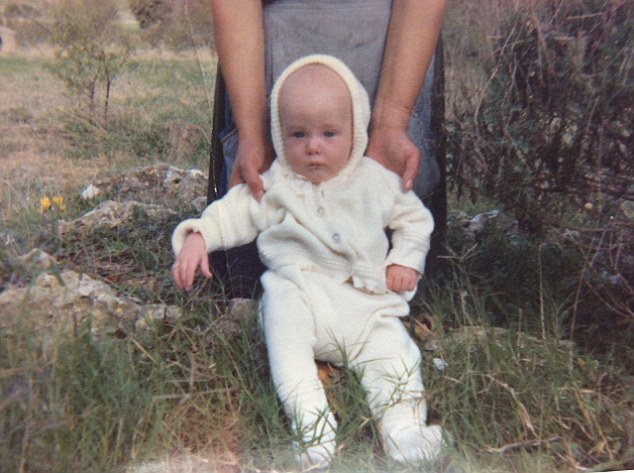

Lost forever: Jennifer Evans' baby girl, aged six months, was taken from her by social workers because she was unmarried

We were told from the start that we would have six weeks with our newborns, and then they would be given to ‘more deserving married couples’.

But I vowed to fight the social workers. For this, I was labelled rebellious, and given the worst jobs, such as cleaning the toilets. The matron told me I had to take 10mg of valium each day, and when I refused, she forced it down my throat.

It was also feared that I might influence the other women and girls, and that they might join me in simply refusing to discuss adoption.

And so I was put in an attic room on my own, far away from them. Once, when I took a shower without permission, the matron yanked me out, naked, and marched me back to my cell.

My breathtakingly beautiful little girl was born in April 1969. I was told not to breastfeed and was bandaged, but I took the bandages off and fed her anyway.

I did manage to keep her — at first. I lied and said the father was coming back for me, and then we would marry, but instead I went home to my mother. But my mother could not bear the shame of an unmarried daughter with a child and after six months kicked me out.

How the Daily Mail reported the adoption scandal last month

I started to realise the hopelessness of my situation and also that my daughter’s future with me looked bleak. I was worn down, and she was adopted when she was ten months old. No one ever told me about any benefits or the possibility of subsidised housing.

When they took my daughter, something froze up inside me. For a long time I couldn’t even cry. And then ten months later on a train to Charing Cross, I had the most appalling panic attack and fell onto the floor unable to breathe.

Much later, I did marry and have three more precious children. But the one I lost is lost for ever.

NOTHING CAN MAKE UP FOR LOST YEARS

Rose Thompson, 58, Leicester

When I got pregnant I was still a child, and so I did what all children do. I didn’t say anything and pretended it wasn’t happening. My mother realised eventually, of course, and I was quickly packed off to Saint Faith’s Home for Unmarried Mothers in Bearsted near Maidstone, Kent.

I was 15 when I gave birth. It was 1971, and as soon as I went into labour, they gave me a wedding ring to wear while I was in hospital. It was ludicrous — I was barely 5ft, had long girlish hair, and quite clearly looked like a young teenager. Yet I had to wear this ring, to spare my shame.

I was admitted to hospital in the early hours and then left completely alone in the labour room, scared out of my wits. I remember there was a clock on the wall: the midwife and nurse didn’t come to see how I was until 7am. My daughter was born at 7.07am.

A couple of weeks earlier, they’d made me sign the adoption papers. When I said I didn’t want to, I was told it was illegal for someone my age to keep their baby. The social workers dictated the letter you had to write explaining why you were giving your baby up.

I saw that letter again two decades later, when my daughter and I were reunited through a search agency. Her adoptive parents had given it to her and she’d kept it. There was something extraordinarily poignant about seeing my childish handwriting.

Last month, the Mail published a series of powerful articles describing the trauma and torment suffered by unmarried women forced to give up their babies for adoption from the Fifties to the Seventies

I never had another child — but at least my daughter is back in my life. I know I have been luckier than some. Yet nothing can really make up for the grief and all those lost years.

I WAS RAPED AT 13 - THEN BANISHED

Jenny Satchell, 66, West Sussex

My son was the product of rape. I was 13 and at home alone in South London when three youths broke in with the intention of taking the money in the gas and electricity meters.

One of them raped me. I knew who he was and he was later arrested. But when the case came up in court, he claimed it had been done with my consent, and he was given three years for burglary only.

It was 1961, and I was sent to a mother and baby home in Tulse Hill, South London, run by the Salvation Army. I was in a dormitory with all the schoolgirls — the youngest there was nine — but I had a difficult pregnancy and was bedridden for most of it.

I’ll never forget how they hid us away when the adoptive parents came to look at the babies. They would close the curtains in my room and lock the door.

I’m fairly sure that they lied to these couples about the age of the mothers-to-be. We were all 16, they said, but of course we weren’t.

My mother signed all the adoption documents, but because I was 14 by the time I gave birth — and for some reason 14 was a significant age — I was allowed the usual six weeks with my son before giving him up. The girls under 14 didn’t even see their babies, and weren’t told their sex. They were simply removed at birth.

I did meet my son later, and we now have a close relationship. But my life has been very difficult, and full of heartache. Looking back, I think this incident in my childhood made me believe that I was a bad person, and deserving of bad luck. It shaped me.

I WAS ADOPTED FOR JUST £2

Dave Sykes, 63, Worcester

I was born in Liverpool in 1951 and I grew up knowing I was adopted. My childhood wasn’t cruel, but I was made to feel different, a bit like a lodger or a guest, as though my adoptive parents expected constant gratitude. I really began my search for my mum in 2008, when both my adoptive parents were dead — and it was with a sense of both joy and dismay that I discovered she’d been living just six miles away from me all my life. Six miles!

My mother was 20 when she had me, and single — though six months later, she did marry my father.

Despite her relative maturity, she didn’t sign the adoption papers herself. Instead it was arranged by her very devout parents, and she was given no choice at all.

My adoption appears to have been orchestrated partly through the Church: mum’s parents paid £2 to the people who arranged it, and my adoptive parents paid two guineas, or £2.10.

But mum wanted me back. Once she was ‘respectably married’, she tried to overturn the adoption, but was told it was too late. Instead, when her parents died, she bought their council house — which was the address on all the adoption papers — and simply stayed there until I found her.

She always said: I’m going nowhere until he comes back.

And now I have a wonderful new family. I have two full siblings, a brother and a sister, and my lovely 84-year-old mother, whose long wait finally paid off for all of us. I have been welcomed into her life, and my three children have in turn embraced her.

REUNITED ONLY TO BE REJECTED

Susan Blacktopp, 59, Suffolk

I was born in 1955 to an unmarried mother in a mother and baby unit in Kent.

She was 20, and she kept me for the allotted six weeks before putting me into a children’s home in Felixstowe, Suffolk. At the age of nine months, I was adopted by a loving couple who desperately wanted a daughter. I was lucky.

Throughout my childhood, however, I dreamt of my real mum and built up a great myth around her. I put her on a pedestal and imagined that she loved me dearly.

When the law changed in 1975, and adopted children were given the right to see their original birth certificates, I eagerly started to search for my mother. And that’s when all those silly dreams were shattered, for when I found her, she did not want to know me, still less meet me.

This second rejection was almost too much to bear. Over the past few years I have started to realise just how big an issue adoption has been for me.

I love my own five children fiercely — but throughout my life I have been unable to love another adult, or even understand that kind of love. I have been married four times.

Adoption may sometimes be necessary, but the way it was done then was desperately cruel. Twice in the space of nine months, I was taken from everything I knew and given over to strangers.

It was bound to have a profound effect on me.

Interviews by Alison Roberts

THE DAY I MET MY MOTHER WAS THE DAY SHE DIED

Separated: Su Chantry with her mother

Su Chantry, 47, from Oxfordshire

I always knew that I’d been adopted. I also knew that my real mum’s surname was Chantry: I’d fantasise that she was a French princess and one day I’d go back to her and live in a castle.

In fact, she was 17 when she had me, in a home for unmarried mothers in Lincoln in 1968. She was forced to give me up after six weeks, and it had a devastating psychological impact on her. She had no more children.

When I had children of my own, I desperately wanted to find her and after contacting social services, we were eventually put in touch. She was living in Peterborough and I was in Oxford. Though we were both delighted to have found each other, we were also wary. A second separation would have been too much to take.

And so for years we simply wrote to each other and occasionally spoke on the phone. Somehow it was never the right time to meet — though when I got divorced, I took her name, that name of my childhood dreams: Chantry.

The day I met her in the flesh was the day she died. I knew she was ill, but not how seriously — she had protected me from that — and when I got a call from the hospital to say that she was near the end, I felt a sense of great panic.

I drove to Peterborough praying that I would get there in time. And it was astonishing: the nurses took one look at me and led me to her, the family resemblance was so strong.

She was sedated, but she knew I was there. I sat with her for 14 hours and told her again all about my life and my love for her.

I read to her all the letters we’d exchanged, and I didn’t leave her side for a second: she’d held me for the first six weeks of my life, and I held her for the last moments of hers.

I told her to feel no guilt and that I admired her courage.

Afterwards, when I registered her death, it felt like our journeys had come full circle. The tragedy is that society’s misplaced judgement meant we missed a lifetime together.